Inside Prysmian’s FOS optical fibre plant, where the internet’s backbone is born

At this factory near Naples, improving efficiency and innovation is all in a day’s work

At this factory near Naples, improving efficiency and innovation is all in a day’s work

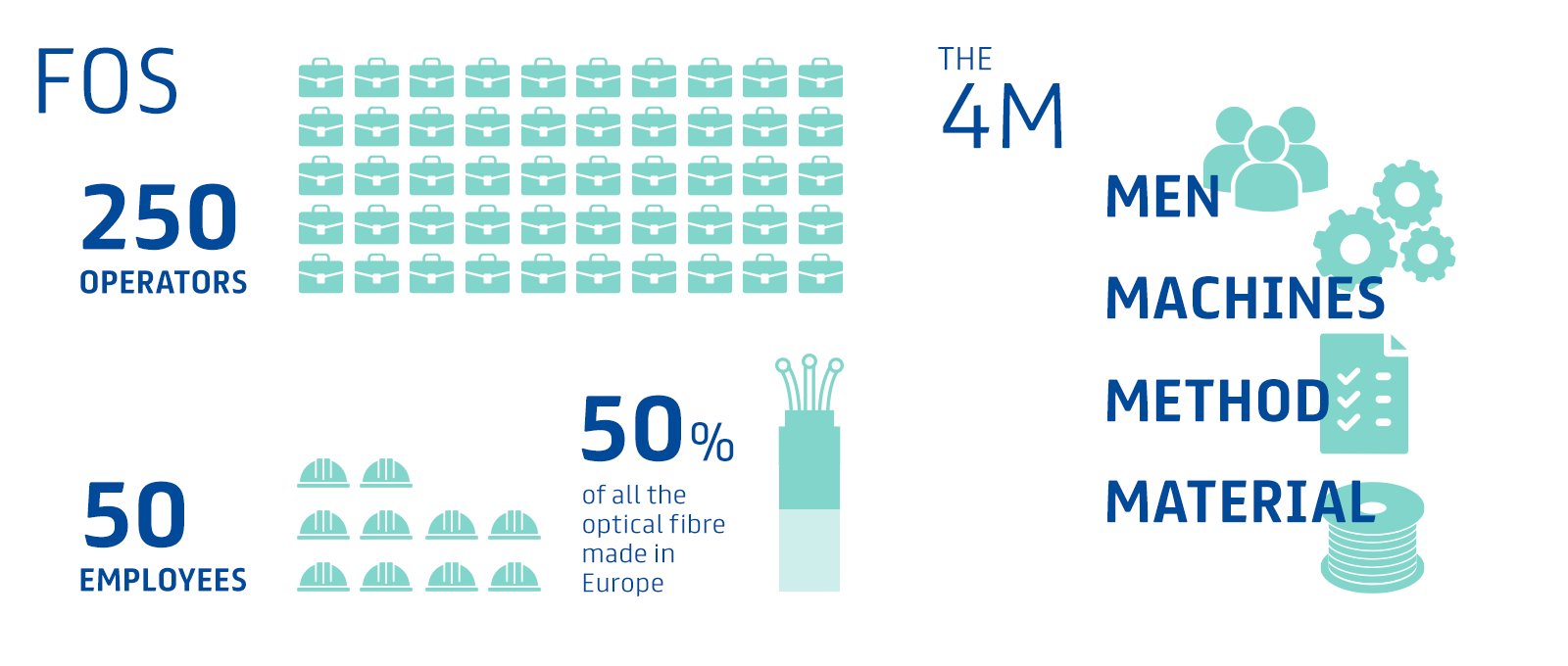

Nicola Scafuro says he often points out the Fibra Ottica Sud (FOS) optical fibre plant to his wife with pride when he sees it from a distance. Rightly so. The optical fibre plant is one of Prysmian’s three fibre plants in Europe, and Scafuro, its general director, is in charge of making sure this cutting-edge factory stays competitive in all aspects of the complex production process. FOS produces about 50% of all the optical fibre made in Europe by Prysmian Group. Prysmian is Europe’s largest producer of optical fibre.

The “drawing tower” is the heart of the FOS optical fibre production, where glass made at the factory is melted and dripped (or “drawn”) into the hair-thin fibres that form the cable backbone of the internet across the world – and that will deliver on the promises of 5G networks and make the “gigabit society” into a reality.

Scafuro and his 300-strong staff have expanded the plant and are making other big changes in order to churn out more and more fibre to meet demand for the smart networks of the future that will power things like data centres, the Internet of Things and self-driving cars. Surprisingly, this outpost of the gigabit society is not in Italy’s industrial north, and is the only factory in the area. Across the road is a kiwi farm. Drive a few kilometers along the two-lane SP 135 highway and you will find Feudi di Terre d’Otranto, a wine producer. The nearest town is Battipaglia, famous for its mozzarella cheese.

The factory was expanded recently, and another expansion is in the works. Prysmian’s achievement at FOS is remarkable not just because it mixes the gigabit society with kiwis, cows and vinyards. Scafuro and his staff’s continual commitment to excellence means that FOS improves its competitiveness each year, in terms of both product development and factory efficiency.

For example, FOS has an in-house R&D team, as part of the Business Unit Optical Fibers R&D, which invented the most advanced fibers applying for many patents. “We think that having an R&D staff right here in the factory, and under the guidance of headquarter’s teams, is a big plus since development time is getting tighter and tighter,” he said.

This commitment to continual improvement is driven by people, not machines. It comes from the dedication of the 250 employees and 50 engineers who work at FOS, from the workers and technicians on the factory floor to researchers and managers.

“What I found here was that Prysmian gives you the strength and energy to face daily challenges,” said FOS director of production Marco Giordano, 39, who is responsible for production from start to finish. “It is not just a slogan but something that happens every day in terms of a mindset. To see that the company is always supporting you gives you the strength to make sacrifices to meet new challenges.”

FOS was built in the late 1970s as a joint venture between Pirelli, the cable and tire maker, and Sirti, a state-owned installer company. In 1983 it began to produce optical fibre using Corning’s Outside Vapor Deposition (OVD) under license.

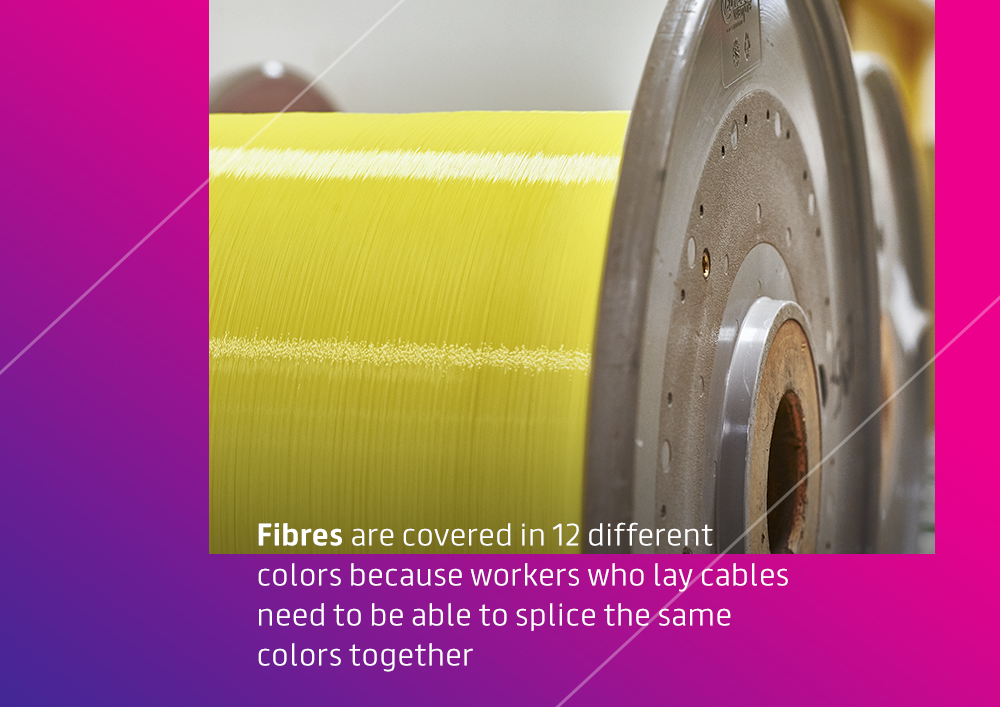

The OVD process uses a flame to produce silica (which is the most common ingredient in sand and in glass) starting from a liquid. Small particles of silica soot are deposited on a rod rotating in a lathe, creating a white oblong shape called a “soot preform.” At this point, the soot preform has the consistency of powder, and will crumble if touched. After that, the preform is heated to form a solid tube of incredibly pure glass. Then it is inserted into the tall “drawing tower” where it is heated until it melts and drip by drop is formed into fibre, and rolled onto a bobbin. After that, it is sent to quality control testing. Then bobbins go to other Prysmian plants and other customers to be made into cables.

Making fibre is a high-energy process, given the white-hot temperatures of the furnaces and the fact that they are always on. FOS produces its own energy at a trigeneration plant, which simultaneously generates electricity as well as both heating and cooling from the combustion of methane, explains Carlo Lubrano, head of finance and control. The system is efficient because it uses “waste” heat to generate cold and steam.

The factory’s staff has one main focus: making sure this production process is as efficient as possible by reducing waste, both of raw materials and of human resources. Marco Giordano and function managers start their day each morning with a trouble-shooting meeting to make sure everything is on track. The lathes and ovens run around the clock, and only stop for heavy maintenance nine days a year over the Christmas holidays.

Clearly it’s not enough for nothing to “go wrong.” It has to be “right first time.” The plant must continually improve, as Process Engineering Manager Giovanni Ruggiero explained. “The key to success was a strong collaboration between process engineering, maintenance and production,” he said.

The R&D department plays a big role is helping FOS wring out more efficiency and lower costs – which is particularly important as new competitors from low-cost labor countries come onto the market.

The plant is currently preparing to switch over to larger preforms, which will give a big boost to efficiency. But it also means that Irene Di Giambattista, an R&D engineer, and her colleagues have to redesign the entire production process.

“Each day we are working to find the optimal result,” she said.

The same could be said about FOS.